Sunday, April 30, 2017

Monday, April 24, 2017

Dear Florida Legislators

RE:

SB 150 / HB477

As lead organizer of the grassroots community

organization Suncoast Harm Reduction Project, I wish to make the position of

the mothers and families in our community known re: HB 477 / SB 150.

We stand in opposition to both these bills

unless amended to include judicial discretion.

I lost both my sister and my mother to

accidental overdose. I’ve witnessed my son spend 5 days on life support and

then get up and use drugs again. I’ve been to court maybe 50 times with family members

dealing with drug related “crimes”.

Reading this you may find it counterintuitive that I, our organization,

and most of the families we’ve worked with stand against the current Florida

legislation promoting tougher sentencing in the face of our opioid overdose

crisis.

Our collective up close and personal

experiences with the ravages of addictive illness have taught us that more

punitive incarceration is not the answer. As more families become affected by

opioid use, many parents have educated themselves, concluding that we need to

treat this medical disorder as a public health crisis. History shows that

supply never drives demand. Assuming the intent of these bills is to combat

addictive illness, we view these bills as strictly supply interdiction, and

having no effect on the public health crisis. This approach equates to

ineffective use of taxpayer dollars.

In 2015, there were 1,488,707 arrests for drug

law violations. As a country, we are now dealing with the overincarceration of

drug offenders. Those convicted of drug

charges are subject to exclusion from public benefits, housing, college grants,

employment and even voting. Cycling in

and out of the criminal justice system and resulting barriers to social

services has become the greatest roadblocks to sustained employment and

meaningful recovery.

Despite theories that mandatory minimums will

target only those selling specific substances, in practice nearly every

individual suffering from addictive illness finds it necessary - at some point

- to engage in behavior that is often

construed as sales. The resulting mandatory minimum sentences imposed on

vulnerable populations in need of health services creates long term familial

and community voids – these communities report increased violence, which also puts

law enforcement at greater risk of harm.

Increased penalties of the “crack epidemic”

taught us that longer, tougher sentences and mandatory minimums did more harm

than good. Families of color were disproportionally affected, even though rates

of drug use show no racial disparities.

What

is their goal in this overcriminalization?

If it is to curb drug use, it has proven to have gotten worse over the

past 45 years after 1 trillion+ dollars spent.

Can Florida afford to spend a million dollars locking up one person for

life rather than investing in the community with treatment and other

life-saving resources? In

Florida prison spending continues to rise, while spending on addiction

treatment is gutted.

We urgently call for health-oriented

strategies to stop the irresponsible waste of lives, dollars and resources.

Julia Negron, CAS

Suncoast Harm Reduction Project

Sarasota / Manatee counties

www.floridashrp.org

Thursday, March 24, 2016

Wednesday, May 13, 2015

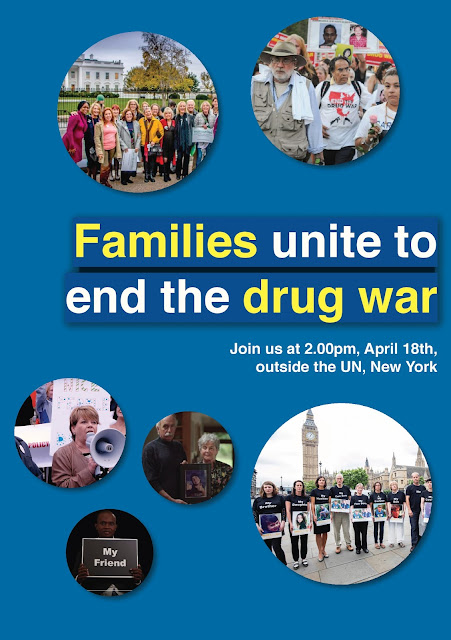

Moms united to end the war on drugs

Moms united to end the war on drugs Mothers, family members, healthcare professionals and individuals in recovery are joining together to bring focus to our country's failed drug policies and the havoc they have wreaked on our families.

Moms United to End the War on Drugs is a growing movement to stop the violence, mass incarceration and overdose deaths that are the result of current punitive and discriminatory drug policies. We are advocating for therapeutic drug policies that reduce the harms of drugs and current drug laws. The figures are staggering:

Overdose: In the US, men aged 35-54 are more likely to die of a drug overdose than a car accident. In 2006, the latest figures published by the Centers on Disease Control, 26,400 people died of an unintentional drug overdose in the US. And, yet, because of punitive drug laws, people who witness an overdose are often too afraid to call for help.

Arrests: Over 1.8 million people in the US were arrested for a drug offense in 2008, 1.4 million of them for drug possession – not sales or trafficking. A disproportionate number of these arrests are of

people of color, particularly young African-American men, even though drug use and sales rates are comparable across racial and ethnic lines.

people of color, particularly young African-American men, even though drug use and sales rates are comparable across racial and ethnic lines.

We encourage you to join Moms United to End the War on Drugs, a campaign of A New PATH (Parents for Addiction Treatment & Healing) in partnership with a growing number of organizations and individuals in a massive collaborative effort to change our current punitive policies of arrest and imprisonment to health-oriented and therapeutic strategies.

Keep up-to-date with drug policy developments by subscribing to the IDPC Monthly Alert.

Friday, April 10, 2015

Hitting Bottom on the Politics of Punishment: Needle Exchange and the Costs of Inaction

I think it’s time for harm reduction advocates to reclaim the word “enabling.” True confession: I got into harm reduction to enable people who use drugs. I enable them to protect themselves and their communities from HIV and hepatitis C and overdose. I enable them to feel like they have someone to talk to, someone who cares, someone who respects them and their humanity. I enable them to ask for help and to help others in turn. I enable them to find drug treatment and health care, to reconnect with their families, to rebuild their lives. And I enable people who use drugs to take personal responsibility for their health and their futures. If that makes me an enabler, I’m proud to claim that term.

But in a lot of addiction rhetoric, enabling is a dirty word akin to aiding and abetting addiction — conspiring with the enemy. It’s based on the creed that a person struggling with drugs has to “hit bottom” and suffer enormous loss and intolerable pain before they’re ready for help. Never mind that research actually contradicts the “hitting bottom” model; too many addiction counselors and self-styled experts still consider it an article of faith and warn us in dire terms against enabling. Does someone in your life have a drug problem, and you don’t want to cut them off, break up with them, fire them, kick them out? You’ll be accused of enabling them by interrupting their trajectory towards hitting bottom.

It’s a cruel philosophy that has caused immeasurable damage, both to people who use drugs and those who love them. Parents, partners and families seeking help and support have been taught the gospel of enabling, held responsible for their loved ones’ addictions, and blamed for their relapses. The taboo against enabling aims to strip away any and all forms of support, compassion, and aid for people who use drugs. Those who preach against the evils of enabling are deeply, almost sadistically, invested in seeing people who struggle with drugs isolated, and punished, as if they’d somehow be purified through suffering. No matter if that punishment takes the form of a fatal overdose — at least nobody enabled them.

The toxic mythology of enabling and hitting bottom seeps into public policy debates, most notably around needle exchange programs. Lawmakers fret that needle exchange is another form of enabling, sending the wrong message and encouraging drug use. 25 years of working in and with needle exchange programs has taught me a different lesson: needle exchange programs restore personal responsibility and enable people to seek help and recover from addiction.

An effective program gives people who inject drugs a chance to take responsibility for their risk of HIV, hepatitis C, overdose and addiction by seeking help and support. This responsibility extends beyond self-interest; in my experience, people who come to needle exchange programs care deeply about protecting the health of their friends and partners, families and communities. The best programs open the door to health care and drug treatment to those who had given up hope and succumbed to fatalism and shame. Needle exchange is our best early intervention for people who inject drugs, before they show up in jail — or the morgue.

This vision of needle exchange gradually seems to be persuading politicians and policymakers in places that have traditionally not embraced harm reduction. In Indiana, an HIV outbreak linked to painkiller injection is upending the traditional politics of needle exchange. Indiana’s Governor Mike Pence spoke of “a commitment to compassion” to justify an executive order making limited allowance for a temporary needle exchange program in Scott County. And last month, Kentucky passed a comprehensive heroin billwhich included a provision allowing local health departments to establish needle exchange programs.

Needle exchange had been a major point of contention in 2014, when Kentucky lawmakers failed to pass a similar bill. This year was different: Kentucky’s growing heroin problem and the sustained advocacy of parents’ groups and people in recovery made clear that inaction was unacceptable. In the final hours of debate, one state senator invoked Thomas Aquinas to explain his opposition to the bill’s needle exchange provision. Aquinas praised the use of the death penalty “if a man be dangerous and infectious to the community, on account of some sin.” But the opioid epidemic is leading more lawmakers to reject the notion that death, whether quickly from overdose or slowly through infection, is a fitting penalty for heroin use. The senator’s argument to “let the punishment fit the crime” did not persuade his colleagues, who overwhelmingly voted in favor of the bill on a bipartisan basis.

In Indiana, outside of the county covered by the Governor’s declaration of public health emergency, needle exchange remains otherwise illegal, despite rising heroin use and hepatitis C infections across the state in recent years. Governor Pence has so far rejected calls for broader needle exchange legislation, but should consider the price of inaction. Each of the nearly 90 newly infected people identified so far by Indiana health officials will need to begin lifelong treatment with antiretroviral regimens. In most cases, their HIV care and prescription drug costs will be covered by the government through Medicaid and the Ryan White Program. A recent study found thatpreventing a single HIV infection saves roughly $230,000 in lifetime medical expenses. In other words, the cost to taxpayers of Indiana’s prevention failure runs to over $22 million. By comparison, in 2008 the combined annual budget of over 120 needle exchange programs across the country wasonly $21.3 million.

Costs also factored into Kentucky lawmakers’ support for needle exchange, with prescription opioid and heroin injection driving a dramatic rise in new hepatitis C infections. Hepatitis C, like HIV, is a virus transmitted through shared syringes and injection equipment. Northern Kentucky now has thehighest rate of new hepatitis C cases in the country, mostly among young people in their 20s. With new hepatitis C treatments priced at over $80,000, the economic case for prevention through needle exchange takes on great salience for states struggling to absorb the costs of these medications in their Medicaid budgets.

Similar financial considerations have led a growing number of conservatives to rally around criminal justice reform. The Right on Crime Initiative has galvanized bipartisan reform efforts by insisting on rigorous accountability and cost-effectiveness standards in sentencing, corrections and public safety. Needle exchange programs fall squarely within these criteria, not only by preventing infections but also by reducing costs and overall drug use. Injection drug use is strongly associated with criminal justice involvement, and indeed several infections in Indiana’s HIV outbreak were identified among inmates of Scott County’s jail. Alternatives to incarceration for people who use drugs are now a cornerstone of criminal justice reform across the political spectrum.

Yet needle exchange still faces deep reservoirs of suspicion and outright opposition. To opponents, needle exchange represents the worst case scenario for so-called government handouts — taxpayer dollars subsidizing (read: enabling) addiction. We have abundant evidence that needle exchange does not increase nor encourage drug use, but the false specter of “enabling” looms over the policy debate. This logic underwrites the federal funding ban on needle exchange programs, championed for many years by former Indiana Congressman Mark Souder. The federal funding ban has starved needle exchange programs of both resources and legitimacy, relegating them to the margins of the health care and drug treatment.

Against these odds, needle exchange programs still managed to dramatically lower HIV rates among drug injectors, and were showing similar success in reducing hepatitis C infections until the opioid epidemic and a resurgence in heroin resulted in a 75% jump in new hepatitis C cases in only two years. This is a clear signal that we need more needle exchange in more places, particularly places like Indiana and Kentucky. And we need them now, before we see more HIV outbreaks.

Perhaps the convergence of compassion and cost-effectiveness will produce a reappraisal of needle exchange policy. In public health terms, the Indiana HIV outbreak is a sign that we may be hitting bottom on the bankrupt policies and ideological stalemates that have held us back. We need more needle exchange because we need to enable communities to take control of their drug problems using all available strategies.

When I spoke recently at a harm reduction summit in Ohio, I described working in a needle exchange program as a little like going to church: it requires humility, faith, and openness to moments of grace. Working on harm reduction policy is a lot like working in a needle exchange program. My deepest hope is that Kentucky’s legislation marks a turning point in our approach to drug use and harm reduction. We are already absorbing the staggering costs — human, financial, and moral — of our rejection of needle exchange. Our families and communities — and all those caught up in the prescription opioid and heroin epidemic — cannot afford to bear the punishment for the crime of our policy failures.

Tuesday, March 31, 2015

To Save Lives, Give Drug Users the Overdose Antidote

By Tessie Castillo / AlterNet

June 13, 2014

Photo Credit: Photographee.eu / Shutterstock.com

As drug overdose

continues as the leading cause of accidental death in the United States

For decades paramedics

have administered naloxone to patients experiencing opioid overdose. About 20

years ago overdose prevention advocates realized that naloxone would save more

lives if programs could distribute it to active drug users. The Chicago Recovery

Alliance is credited with creating the first organized naloxone distribution

program in 1996, but a decade before that, a couple of rogue paramedics in Oakland , California

During the 1980s, Oakland Sparks

Opioid overdose

stops a person’s breathing, which can result in brain damage or

death. Naloxone works by temporarily blocking the effects of opioids,

thereby restoring normal breathing. Before receiving naloxone, Sparks

While people are often

hesitant to call the authorities for fear of legal ramifications, the official

recommendation is to call 911 to report an overdose even if naloxone is on

hand. Because naloxone only temporarily blocks the opioids, the person could

overdose again after it wears off and might need followup medical care. Rescue

breathing is also recommended until the person can breathe on their own.

After his first naloxone

rescue, Sparks

“After they left, I went

back to rescue breathing [when someone overdosed] because I didn’t know where

to get naloxone,” Sparks

It would be almost 15

years before someone else realized what those Oakland

“I’m alive today because

of naloxone,” said Kinzly, who has overdosed twice. “If we are going to make a

difference in preventing overdose deaths, we need to get naloxone to the drug

user community.”

This summer Georgia

This July, AHRC plans to

introduce a naloxone distribution program modeled after a program at North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition that

has reported 80 overdose reversals by laypeople since August 2013 Thirty years

after paramedics gave him his first dose of naloxone, David Sparks is now 10

years drug-free. In his free time he volunteers with one of California

“No one should ever die

of an [opioid] overdose,” said Sparks

To some people, giving

active drug users the tool to reverse overdose might be a new or even

controversial idea. But as Sparks

To find the naloxone

distribution program near you, visit the program

locator. Or learn more about how to start a naloxone program.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)